Disadvantaged children born at the start of the 21st century weighed up to 5kg more in their childhood and early teenage years than those from more privileged backgrounds, a new study has found.

Disadvantaged children born at the start of the 21st century weighed up to 5kg more in their childhood and early teenage years than those from more privileged backgrounds, a new study has found.

Yet in previous generations lower social class was associated with lower childhood and adolescent weight. As a result of these changes, social class inequalities in obesity emerged and widened at the end of the last century.

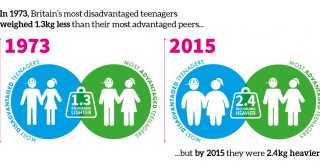

In 1973, Britain’s most disadvantaged teenagers weighed an average of 1.3kg less than their most advantaged peers. However, by 2015, teens from the most disadvantaged backgrounds weighed an average of 2.4kg more than the most privileged.

The findings, published today (21 March) in The Lancet Public Health suggest that Britain’s obesity epidemic has had a much greater impact on the country’s less well off.

Funded by CLOSER, researchers from UCL compared the childhood and adolescent social class, weight, height and BMI of British children from four different generations for the first time.

It is the second study to use three harmonised datasets, created by CLOSER in 2017, which contain comparable measures of height, weight and BMI from separate longitudinal studies.

Their findings revealed that for children born in 1946, 1958 and 1970 their social class made little difference to their BMI at ages 7 or 11. However, for the children born in 2001, there were socioeconomic inequalities: those with from a lower social class were more likely to have a higher BMI and that the higher the BMI, the wider this socioeconomic inequality was.

The authors say that these trends highlight the powerful influence that an environment encouraging consumption of a high-calorie diet and discouraging physical activity has had on socioeconomically disadvantaged children.

“Our findings illustrate a need for new effective policies to reduce obesity and its socioeconomic inequality in children in the UK – previous policies have not been adequate, and existing policies are unlikely to be either,” says lead author Dr David Bann, of the Centre for Longitudinal Studies at the UCL Institute of Education.

“Without effective interventions, childhood BMI inequalities are likely to widen further throughout adulthood, leading to decades of adverse health and economic consequences.”

David added, “Our results illustrate a need for strong additional legislative changes that focus on societal factors and the food industry, rather than individuals or families. Bold action is needed, such as creating further incentives for food manufacturers to reduce sugar and fat content in food and drinks, reduce the advertising of unhealthy foods to children and families, and incentivise the sale of healthier alternatives. The Soft Drinks Industry Levy is a positive but likely very limited step in the right direction.”

The study included data for children born in England, Scotland and Wales from four longitudinal birth cohort studies: the 1946 MRC National Survey of Health and Development, 1958 National Child Development Study, 1970 British Cohort Study and Millennium Cohort Study.

At the ages of 7, 10/11 and 14/16 years old, the children’s height and weight were measured, and BMI was calculated. The child’s father’s occupation was used as a marker of their socioeconomic position, and the association of socioeconomic position with weight, height and BMI was analysed from childhood and adolescence.

‘Socioeconomic Inequalities in Body Mass Index, Weight, and Height in Childhood-Adolescence from 1953 to 2015: Findings From Four British Birth Cohort Studies’ by David Bann, William Johnson, Leah Li, Diana Kuh and Rebecca Hardy was published by The Lancet Public Health on 20 March 2018.

The research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Medical Research Council (MRC).

Read more about data harmonisation.