Society today is facing a number of multifactorial problems with no one single cause and no simple solution. That’s why on 28 June, we are bringing together a panel of leading scientists to talk about their studies and how longitudinal research can help get to the heart of ‘wicked’ problems.

Don’t worry if you can’t be there in person – you can follow the proceedings via Twitter using the hashtag #EvidenceWeek. And for more on our longitudinal studies and the treasure trove of evidence generated from these world-class research resources, check out our website.

The UK’s portfolio of longitudinal studies span over 80 years and involve more than 2 million participants. They engage with the same people over time, sometimes from birth, to help us understand the complexity of people’s lives, how those lives are changing, and how early life circumstances and experiences affect later life. Which is one of the reasons why (as the home of longitudinal research) CLOSER is involved in ‘Evidence Week’, an initiative of Sense about Science, the House of Commons Library, Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology and House of Commons Science and Technology Committee.

The first of its kind, Evidence Week runs from 25th to 28th June 2018 and will bring together MPs, peers, parliamentary services and people from all walks of life from across the UK to talk about why evidence matters. In this blog I focus on the value and power of one particular form of evidence – that from the UK’s world-class longitudinal studies.

Longitudinal research can help get to the heart of complex, ‘wicked’ problems facing our society today, enabling policymakers and practitioners to better understand what’s going on in and across generations and develop appropriate policies and interventions. The concept of ‘wicked’ problems was first defined in planning literature by Rittel and Webber (1973) – these are problems that are not linear, have many interdependencies and are often multi-causal, they don’t sit conveniently within the responsibility of any one government department or organisation, and they involve changing behaviour (with all the difficulties that brings!). Ultimately, they are problems that if not addressed properly can have very negative consequences for society.

Obesity is one of the ‘wicked’ problems we are facing today and an area where the UK’s longitudinal studies have already helped inform and influence the debate. In 2015, CLOSER funded research found that children born since 1990 are up to three times more likely than older generations to be overweight or obese by age 10. The research demonstrated that since 1946, every generation has been heavier than the previous one – and worryingly, it is the most overweight people who are becoming even heavier. No other study has been able to track weight gain across as many generations, or through as much of their lives (from age 2 to 64 for the oldest participants in this study), which is why these findings underpinned the first chapter of the Government’s Childhood Obesity Plan.

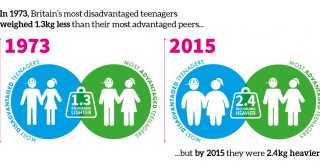

Longitudinal research is also uncovering new challenges in relation to obesity. In previous generations, disadvantage was associated with lower childhood and adolescent weight. However new CLOSER funded research, published this year, found that disadvantaged children born at the start of the 21st century weighed up to 5kg more in their childhood and early teenage years than those from more privileged backgrounds. These findings illustrate a need for new policies to reduce obesity and its socioeconomic inequality in children in the UK, with a focus on societal factors and the food industry, rather than simply individuals or families.

Longitudinal research is also uncovering new challenges in relation to obesity. In previous generations, disadvantage was associated with lower childhood and adolescent weight. However new CLOSER funded research, published this year, found that disadvantaged children born at the start of the 21st century weighed up to 5kg more in their childhood and early teenage years than those from more privileged backgrounds. These findings illustrate a need for new policies to reduce obesity and its socioeconomic inequality in children in the UK, with a focus on societal factors and the food industry, rather than simply individuals or families.

To me, the longitudinal evidence on obesity is clear – the powerful effect of an obesogenic environment on our children, particularly socioeconomically disadvantaged children, is stark. However, addressing that alone will not stop the rise in childhood obesity seen in the longitudinal research. Measures that focus on the pre-conception period and early years, educating mothers, increasing physical activity, reducing sugar and fat content in food and drinks, reducing the advertising of unhealthy foods to children and families, and incentivising the sale of healthier alternatives are all needed if we really want to tackle the problem.

The second chapter of the Government’s Childhood Obesity Plan was published this week. Whilst many have already criticized it for not going far enough, its multi-level focus marks a step-change in approach, which should be welcomed. Measures include efforts to reduce sugar content and calorie intake, more transparency to help parents make informed choices, limiting children’s exposure to products that are high in fat, sugar and salt and empowering local authorities and schools in creating a healthy environment for our children.

It’s not, and never will be, a silver bullet, but this latest chapter begins to bring in other elements, moving towards a more comprehensive approach than seen before. However, I would have liked to see more of a focus on prevention, the early years and reducing risk factors during pregnancy, including poor educational attainment, smoking and diet. Crucially, this should not be laid at the feet of the Department for Health and Social Care alone – the need to work across government departments and agencies to tackle this and other ‘wicked’ problems is clear. Calling it a ‘second chapter’ also indicates to me that it is the next step in the process and when new evidence comes to light and the long-term impact of initiatives such as the Daily Mile are measured, later chapters will take these into account and adapt to ensure the ongoing fight against childhood obesity is not lost.

Rob Davies is Public Affairs Manager for CLOSER, the home of longitudinal research. You can follow Rob on Twitter: @r0bdavies.

Suggested citation:

Davies R (2018) “How longitudinal research can help get to the heart of ‘wicked problems’”, CLOSER blog.