People working in creative occupations are disproportionately from more privileged social class backgrounds, despite the attitudes and beliefs of the sector. Dr Orian Brook and Dr Dave O’Brien, both Chancellor’s Fellows at University of Edinburgh, and Dr Mark Taylor, Senior Lecturer at University of Sheffield, analysed data from the ONS Longitudinal Study (ONS LS) and found that these exclusions have persisted over decades. They argue that this has implications for how social inequalities are represented and reproduced within our culture, the legitimacy of the sector to portray individuals and society, and the positive value of culture for all of society.

What are the social origins of those working in creative occupations, over time?

The creative economy has been feted as a driver for social mobility, and for the progressive attitudes and belief in meritocracy of its workforce. Recent research has shown, however, that there are significant exclusions in terms of social class, ethnic group and gender, but this was believed by many to be a recent development, driven by political changes including introduction of student fees, increased expectation of working for free, and the increasing cost of living in London all affecting access to creative work.

The data

Orian, Dave and Mark draw on data from the ONS LS to demonstrate that the exclusions from creative work according to social class origins did not change between those born in the 1950s and the 1990s. The ONS LS offered unequalled data to use for this, the first nationally representative analysis of social mobility into creative occupations.

The ONS LS is a dataset of individuals in England and Wales created from a 1% sample of Census returns, chosen using four (undisclosed) birthdays. The ONS LS links records from each Census from 1971 to 2011 (life event data including births, deaths and cancer registrations, although only Census data is used in our study). It has a number of key advantages for this study:

- The large number of individuals is helpful as the number of people in the “core cultural” occupations of interest (artists, musicians and actors, and those working in publishing, media, libraries, museums and galleries) is relatively small, and can be hard to find in sufficient quantities for analysis in smaller datasets;

- standardised coding of key variables such as occupation and educational qualifications is recorded;

- individuals are not only linked between decennial Censuses, but also to other household members. By identifying those who in their first appearance in the Census are living with their parents, it is possible to record a measure of social class origin based on their parents’ occupations when the LS member was aged between 9 and 18.

Specifically, the researchers isolated four cohorts (born 1953-1962, 1963-1972, 1973-1982 and 1983-1992). Each cohort was observed aged 9-18, when the occupations of their parents were used to assess their social class origins, and in at least one subsequent Census when they were of working age. Their aim was to analyse social mobility into core cultural occupations, to investigate whether gender, ethnicity, educational qualifications and living in London as a teenager were associated with working in a core cultural occupation, and to compare these relationships across the four different cohorts.

Findings

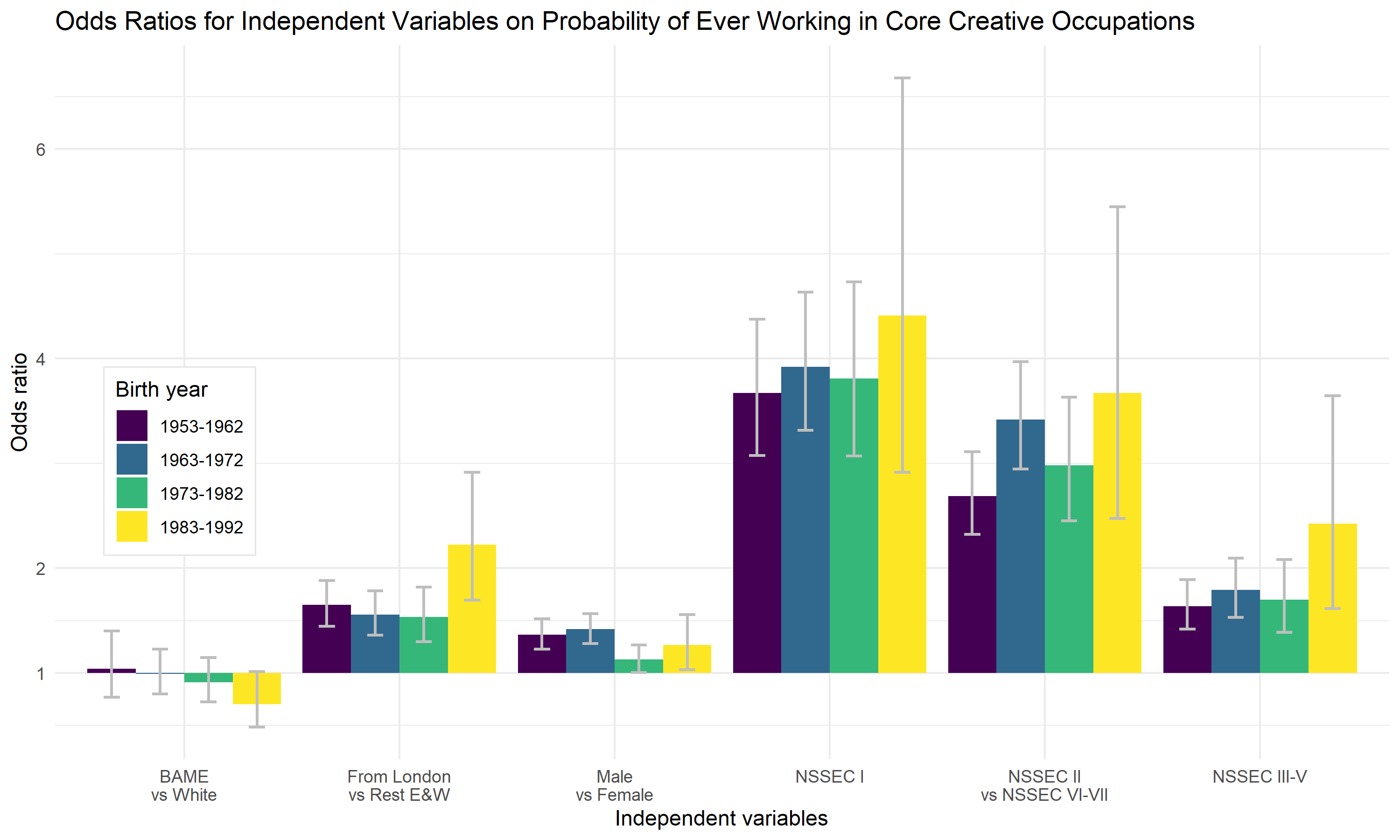

For each cohort, the probability of ever reporting a core cultural occupation was modelled according to parental occupation, coded to NSSEC I for higher managerial and professional (such as doctors and business executives), NSSEC II for lower managerial and professional (including nurses, teachers and middle managers), NSSEC III-V for intermediate occupations (for example small business owners, clerical and technical workers) and NSSEC VI-VII for routine and semi-route, traditionally working class occupations (including cleaners and factory workers), as well as gender, ethnicity, education and living in London. The relationships are shown in the figure below for each cohort, represented by the different coloured bars, with the change in odds associated with membership of each category, compared to its opposite (or, in the case of social class, compared to having working class parents).

The figure shows a clear class gradient in the likelihood of reporting creative work, with those from the most privileged social origins having four times the odds of being a creative worker compared with those from the most disadvantaged background (NSSEC VI-VII). This association is similar across all cohorts. There is also a persistent advantage of being from London, and of being male. There are no differences according to ethnicity until the most recently born cohort, where BAME members have a disadvantage compared to their White peers. The relative lack of disadvantage here is perhaps surprising and does not correspond to the experiences of creative workers we interviewed. This may be partly explained by those from BAME groups being more likely to also have parents classified in more disadvantaged social groups according to occupation. However, measurement of social class of origin for second generation immigrants is problematic as their parents are likely to have experienced racism resulting in exclusion from the higher status work that their qualifications should have enabled.

Impact

If recent government policies have not brought the exclusions from creative work into existence, then they are perhaps associated with issues within the creative sector. Orian, Dave and Mark combined this research with other quantitative data and with analysis of a web survey and 237 interviews with creative workers, to understand how a workforce with strong beliefs in meritocracy produces such socially patterned exclusions. They focused on the experiences of creative workers that had been socially mobile, particularly women of colour, who reported their experiences of the creative sector as a hostile environment. They looked at classed experiences of being expected to work for free, at gendered experiences of trying to parent as a creative worker, and at how men in senior roles from privileged origins were able to lament the social exclusions from their sector whilst ascribing all of the opportunities that they had benefitted from to luck. They discussed these issues, and the impact of these exclusions on the benefit that society accrues from culture, in their book, Culture is bad for you: Inequality in the cultural and creative industries.

This work has been taken up in Arts Council England’s latest 10-year plan by the Policy and Evidence Centre run by NESTA, and is especially relevant to their current work on the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. It is being used in the development of initiatives aimed at widening access to creative work by a number of organisations, including the Imperial War Museum, the Weston Jerwood Creative Bursaries scheme, Museum of London, the campaigning group Space Invaders, and the Scottish Contemporary Arts Network.

Acknowledgements

The permission of the Office for National Statistics to use the Longitudinal Study is gratefully acknowledged, as is the help provided by staff of the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information & User Support (CeLSIUS). CeLSIUS is supported by the ESRC Census of Population Programme (Award Ref: ES/V003488/1). The authors alone are responsible for the interpretation of the data.

This work was also supported by AHRC funding AH/P013155/1 and AH/S004394/1

Further information

- Study profile: ONS Longitudinal Study

- Related blog: 50 years of linking our lives

Dr Orian Brook is a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. Follow her on Twitter: @OrianBrook

Suggested citation:

Brook, O. (2021). ‘Have cultural occupations always been socially exclusive? Evidence from the ONS Longitudinal Study’. CLOSER. 31 March 2021. Available at: https://www.closer.ac.uk/news-opinion/blog/have-cultural-occupations-always-been-socially-exclusive-evidence/