Scientists used historical maternity records as foundation of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study

Uncertainty regarding the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has buffeted our community over the past few years.

GDPR was intended to protect citizen interests: to help ensure citizens were aware of how their information was being used, and to provide a set of rights which would give them some measure of control. It was borne out of the rise of ‘Big Data’, and particularly the dramatic upturn in data being used as a commercial commodity, as well as data breaches resulting from carelessness, malicious intent and state-sponsored actions.

But does this influential new regulation also protect the use of personal data for research in the public interest? Yes, as we explain in our open letter in Wellcome Open Research.

GDPR explicitly protects research interests… for responsible information stewards

Following concerted lobbying from the research community[1], GDPR was designed with a set of research exemptions that individual countries could choose to implement. The new UK Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA) implements these derogations in full. This makes GDPR and the new UK DPA arguably more permissive for research than previous legislation.

It is of great importance to our community that GDPR recognises that any data, no matter what the initial reason for collection, can be used for research. It does, however, put a range of new requirements on all organisations that relate to information stewardship:

- we must know what information we possess

- we must catalogue these information ‘assets’ within registers

- we must set bounds relating to who controls these assets, where they should be stored and how long they should be kept.

In practice, this means that organisations across the EU should be cataloguing the information they hold and deciding whether to keep it or destroy it. But not only might data holders not be aware of GDPR’s research exemptions, they might not recognise the potential worth of the information they hold.

GDPR: it’s not about throwing the baby out with the bathwater

This is possibly the first time that organisations will have reviewed the contents of dusty shelves and store rooms for many years. In these shadowy corners we might find new information of value to researchers, and if these long-lost assets are made accessible to the scientific community, they may help us to answer critical questions about modern life.

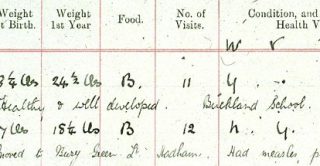

The UK has a rich tradition of using historical information, which had often lay untouched in a basement archive for decades, to establish retrospectively sampled longitudinal studies. Within CLOSER, the Hertfordshire Cohort Study[2] is a fantastic example of this. In the early 1900s, Miss Ethel Margaret Burnside led a team of meticulous midwives and health visitors in Hertfordshire county. They collected detailed information on births in the county between 1911 and 1948, which they recorded in hand-written ledgers. Decades later, these ledgers played a critical role in answering a pressing public health question: why were parts of the country with the least healthy babies 60 or 70 years ago the same parts with widespread heart disease today? Scientists uncovered the Hertfordshire ledgers and were able to use them as the foundation of a longitudinal study investigating the early life predictors of ill health in old age.

But what happens if fear of non-compliance with GDPR leads organisations to destroy such precious resources before their potential is even known?

Windrush – the lost cohort

The sort of records that informed the Hertfordshire Cohort are all too fragile, as their value may not be widely recognised. The destruction of the Windrush generation’s disembarkation records – which came to light as part of the much broader Windrush citizenship scandal – illustrates that important information like this is at risk of destruction. These records were the ideal information to form a retrospective sampling frame for a study of an important generation in the UK’s history. Ostensibly, these records were destroyed for ‘data protection’ reasons.

But GDPR is clear that it would have been permissible to repurpose such records for research purposes. Insights into why some research has a ‘social licence’ to occur, while other initiatives end in public disquiet, suggests that any such data use would need to be made in consultation with the Windrush migrants themselves and to involve them in the decision making process.

Make it known: information can be retained indefinitely to support research in the public interest

It is vital that the research value of data be widely communicated, understood, and that those making decisions regarding retention and repurpose are aware that this has a firm legal basis within GDPR.

To help this process in the UK, we have been working with research funders – primarily with the MRC regulatory guidance centre at the University of Edinburgh and the ESRC’s longitudinal research advisors to help produce clearer guidance. As a result, we are delighted to say, the Information Commissioner’s Office, the DPA regulator in the UK, has changed its guidance to say (for the first time) that information can be retained indefinitely[3].

So spread the word. There is a real risk that important information in your institution is at risk. Under GDPR, all institutions must now have a Data Protection Officer: get in touch with them, raise this as a concern, let them know that GDPR allows data to be retained indefinitely and to be repurposed for research in the public interest. This is the gift of GDPR and we should use it.

Our open letter ‘The destruction of the ‘Windrush’ disembarkation cards: a lost opportunity and the (re)emergence of Data Protection regulation as a threat to longitudinal research’ is currently undergoing peer review with Wellcome Open Research and is publicly available on their open access platform.

[1] Thompson B. Ensuring a healthy future for scientific research through the Data Protection Regulation 2012/0011(COD). Position of academic, patient and non-commercial research organisations – December 2015. Available from: https://wellcome.ac.uk/sites/default/files/ensuring-healthy-future-for-scientific-research-data-protection-regulation-joint-statement-dec15.pdf

[2] Syddall HE, Aihie Sayer A, Dennison EM, Martin HJ, Barker DJ, Cooper C. Cohort profile: the Hertfordshire cohort study. International journal of epidemiology. 2005 Jun 17;34(6):1234-42.

[3] https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/principles/storage-limitation/

Andy Boyd is a Data Linkage and Information Security Manager at the University of Bristol. You can follow him on Twitter (@_andy_boyd).

Suggested citation:

Boyd A (2018) “GDPR: protection or peril for research in the public interest?”, CLOSER blog.